Clinical Trials in the Community Oncology Setting: Positive Impact on Patient Care

May is National Clinical Trials Month. Many patients and advocates have heard about clinical trials, but they may not know what they are. Put simply, a clinical trial is a standardized study of a new medical treatment. Community oncology practices and their patients are frequent participants in such trials, helping to bring new treatments to the market and presenting exciting new opportunities for patients with rare cancers while safeguarded by rigorous safety review processes. Without clinical trials, many medicines and treatments we now take for granted might not be available.

In recognition of community oncology’s leading role in clinical trials, Colleen Lewis, MSN, ANP-BC, AOCNP, vice president, nursing and research for Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute (FCS), and Rose Gerber, MS, director of patient advocacy and education for the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) discussed the positive impact of clinical trials and how they work. The discussion touched on the impact of trials on patient well-being, how patients can take part in trials, how health equity is served by including patients from underserved communities in trials, and how community oncology practices are leading the charge to involve patients in the development of new medicines.

Classic Drug Development Process

The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) drug approval process commonly can take as long as 13 years or more. After pre-clinical testing, there are four phases in the process. A new model for clinical trials, called adaptive trial design, is emerging and takes into consideration the scientific rigor while getting drugs to patients as quickly and effectively as possible.

Phase I

Phase I trials not only include new drugs, but new uses for previously approved drugs.

- Transforms laboratory research to clinical care, known as “bench to bedside”

- Goals

- Find a safe dosage

- Decide how the new treatment should be given

- Average number of participants 15 – 30

- More efficient designs are emerging

Phase II

It is during this phase that the determination of which patients with what diseases or conditions might be proper candidates for the drug under investigation is made.

- Tests the effectiveness of a drug in a larger population (usually less than 100 participants)

- Uses the dose determined to be safe in Phase I

- Narrows the focus to people with specific diagnoses

- Treatment is assessed for effectiveness, as well as additional safety data

Phase III

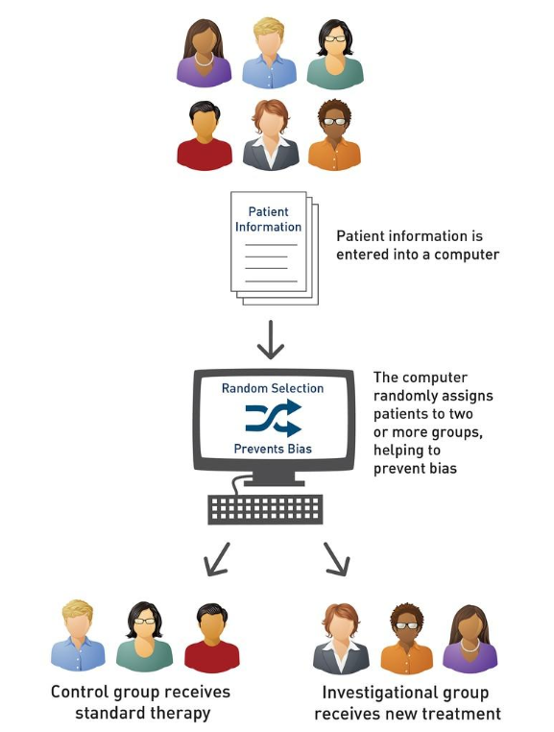

The goal in this phase is to determine if the proposed new drug is better than, or results in fewer adverse reactions than, what is already available.

- Enrolls more patients, often hundreds or thousands

- Compares an investigational treatment to the current standard

- Participants are usually randomly assigned to either the investigational or control group using computer technology to avoid bias

- Trials conducted at multiple sites around the country or the world

Reasons to Decline Participating in a Trial

At this point, it is important to discuss why patients might decline to participate in a clinical trial. Some patients have a fear of side effects or feel that the research, in some cases any drug that is still in the research phase, is too risky. They may also object to the loss of control and are uncomfortable with the idea of a placebo, randomization, or have a desire to retain the ability to select their own treatment. Some clinical trials present logistical challenges, such as an inconvenient location, require too much travel, or involve too much of a time commitment. Others have cost of care concerns, including insurance coverage and costs for additional travel during the trial.

Common Myths

There are common myths associated with clinical trial participation.

- “Must be near a big hospital to take part in a cancer clinical trial” – many community oncology practices offer local, close-to-home clinical trial participation.

- “Clinical trials are a last-resort treatment option” – this is incorrect and clinical trials are often offered as the first and the preferred treatment option.

- “May receive a placebo only, not treatment” – this is incorrect, and patients never receive a placebo in lieu of actual treatment.

- “Participation in trials is not important” – participation in trials advances the discovery of newer, better, safer treatments.

- “More difficult to stay informed during a trial” – trial participants often actually get a higher level of care because of the additional visits and testing required during a clinical trial.

- A frequent misconception is that once in a clinical trial, patients cannot leave the trial; this is incorrect – patients may choose to discontinue participation in a clinical trial at any time.

Phase IV

After FDA approval, new drugs continue to be monitored and evaluated for their efficacy and the occurrence of side effects to ensure that the drugs perform as anticipated.

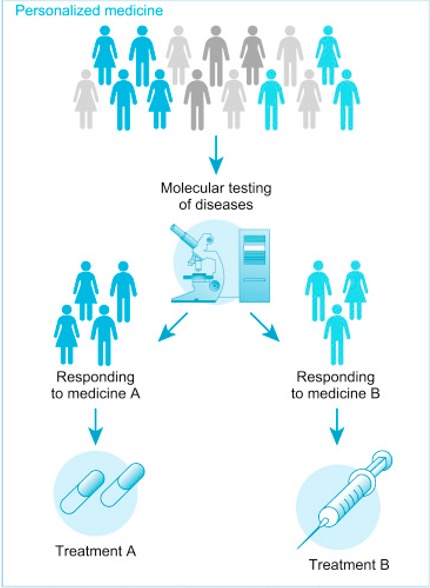

Personalized Medicine

Personalized or precision medicine is a rapidly evolving field focused on how to tailor, as much as possible, the way a patient is medically treated to fit that individual. Information is obtained through several types of testing, often with varying names for the same tests – biomarker testing, genomic testing, and molecular testing. Each test is designed to enable the oncologist to respond to the test results in order to make the most informed treatment plan. One of the first issues being addressed is a standardized naming protocol to increase the clarity of the testing naming.

Over the last seven years, the percentage of precision medicine new drug approvals has ranged from 25 to 42 percent, evidencing the growing preference for personalized medicine.

Patient-Facing Clinical Trial Matching

With the advent of more data, clinical trial matching has become more complex. By leveraging the increased specificity of patient data and through the use of testing results and technology, a match can be found. The process begins with the consideration of all open trials and factors in simple data, such as age, diagnosis, and location. Then the cancer stage and common somatic mutations are assessed. Next, prior lines of therapy, patient comorbidities, and performance status are evaluated. Finally, travel distance and the patient’s preference for the type of therapy are considered. The result is all those clinical trials for which the patient is likely to be eligible for and in which the patient is interested.

There are many steps to biomarker-driven targeted cancer therapy to improve patient outcomes. One of the key considerations is whether the patient’s insurance provides coverage for the tests associated with a given clinical trial. This is an evolving area of advocacy to make legislators aware that these tests are not “nice to have” but are critical components to patient care, clinical trial participation, and hence drug development.

Biomarker Testing & Health Equity

Biomarker test results can drive treatment decisions when considering targeted therapy and/or clinical trial participation. Because there are notable racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access to biomarker testing, health equity becomes an even more important feature of quality cancer care. This can make insurance/payor coverage a limiting factor in care options and thus affect patient prognosis.

States are beginning to introduce legislation to make biomarker testing a covered component of Medicaid coverage and even conventional insurance. These results are critical not only for clinical trial participation, but also for care decisions throughout a patient’s entire active treatment period. There are now many drugs that target certain mutations that are absent from biomarker testing, which patients cannot receive because the mutations have not been identified.

Race and Ethnic Diversity Plan

The FDA is now offering guidance to determine race and ethnicity diversity plans for clinical trials in order to cast a wider net of participants to improve the universality of clinical trial results. This would require sponsors of clinical trials to report to FDA descriptions of:

- Operational measures that will be implemented to enroll and retain underrepresented racial and ethnic participants

- Specific trial enrollment and retention strategies, including but not limited to site location and access, sustained community engagement, and reducing burdens due to trial/study design/conduct

- Metrics to ensure diverse participant enrollment goals

Recruitment

A more diverse patient base for clinical trials must be recruited. Suggestions on how to recruit such a patient base include:

- Design clinical trial protocols along with patients, patient advocates, and caregivers

- Allow patients to access labs and clinics close to home for some research requirements

- Hold clinical trials in locations with higher concentrations of racial and ethnic minorities

- Use electronic informed consent, while considering the needs of patients without internet access

Retention

Once patients are recruited, there must be systems in place to overcome the barriers, such as cost and distance, to continuing participation in the clinical trial. Suggestions for retention include:

- Clinical trial protocols designed with greater input by patients, patient advocates, and caregivers

- Allow access to labs and clinics close to home for some research requirements

- Hold clinical trials in locations with higher concentrations of racial and ethnic minorities

- Use of electronic informed consent, while considering the needs of patients without internet access

Community Oncology’s Role in Clinical Trials

Centered Around the Patient

As a patient at a community oncology practice, participation in a clinical trial offers the benefits of:

- World-class medicine

- Clinical research

- Local access

- Value-based care

Improved Clinical Trial Access

By improving clinical trial access, community oncology can offer:

- Critical components to advancing health equity

- Increase community-based research availability

- Increased availability in rural and underserved areas

- Utilization of technology for trial searching and matching and trial conduct

- Increased access to biomarker testing through legislative advancements

June Advocacy Chat

CPAN Advocacy Chats are regular virtual 30-minute educational conversations about cancer advocacy and policy with a guest speaker invited to discuss issues important to advocates. Do not miss the next Advocacy Chat:

Cancer Survivorship – The Impact on Mental Health

Wednesday, June 21 at 12:00 p.m. ET

The guest speaker will be:

Diane Simard, Founder

Center for Oncology Psychology Excellence (COPE)

University of Denver

CPAN Advocacy Chats are regular virtual 30-minute educational conversations about cancer advocacy and policy with a guest speaker invited to discuss issues important to patients and advocates. Summaries of previous Advocacy Chats are available on the CPAN website.

Past Advocacy Chats